In 1999, eight years before Apple’s first iPhone release, a Silicon Valley software startup named Confinity introduced what it called a new “killer app.” It was dubbed PayPal.com.

The service allowed the “beaming” of funds between users, with only an email address. “Beaming Money by Email is Web’s Next Killer App,” Confinity said in its press release pitch, describing the technology.

The money-by-email effort arose from an earlier Confinity concept to transfer funds using infrared beams. The company demonstrated its payment feat by transferring $3 million with Palm Pilot devices in a breakfast display dubbed “Beaming at Buck’s” in the summer of 1999 at Buck’s, a Woodside, California, restaurant. Max Levchin, the startup’s co-founder, recounted the story several years later in a talk at Stanford University with his Confinity co-founder, Peter Thiel.

A quarter-century on, what began as a pioneering effort to encrypt money and move it digitally has morphed into a global payments industry anchored at the consumer level with digital wallets worldwide on billions of mobile phones. The mobile wallet has become standard for many consumers, some of whom consider a plastic payment card as outdated as a landline phone.

Regulators are still struggling to catch up with financial technology innovators. While the Biden administration tried to impose new oversight on big tech providers of digital wallets and peer-to-peer payments — such as Apple, Google and PayPal Holdings — the Trump administration has reversed that regulatory course.

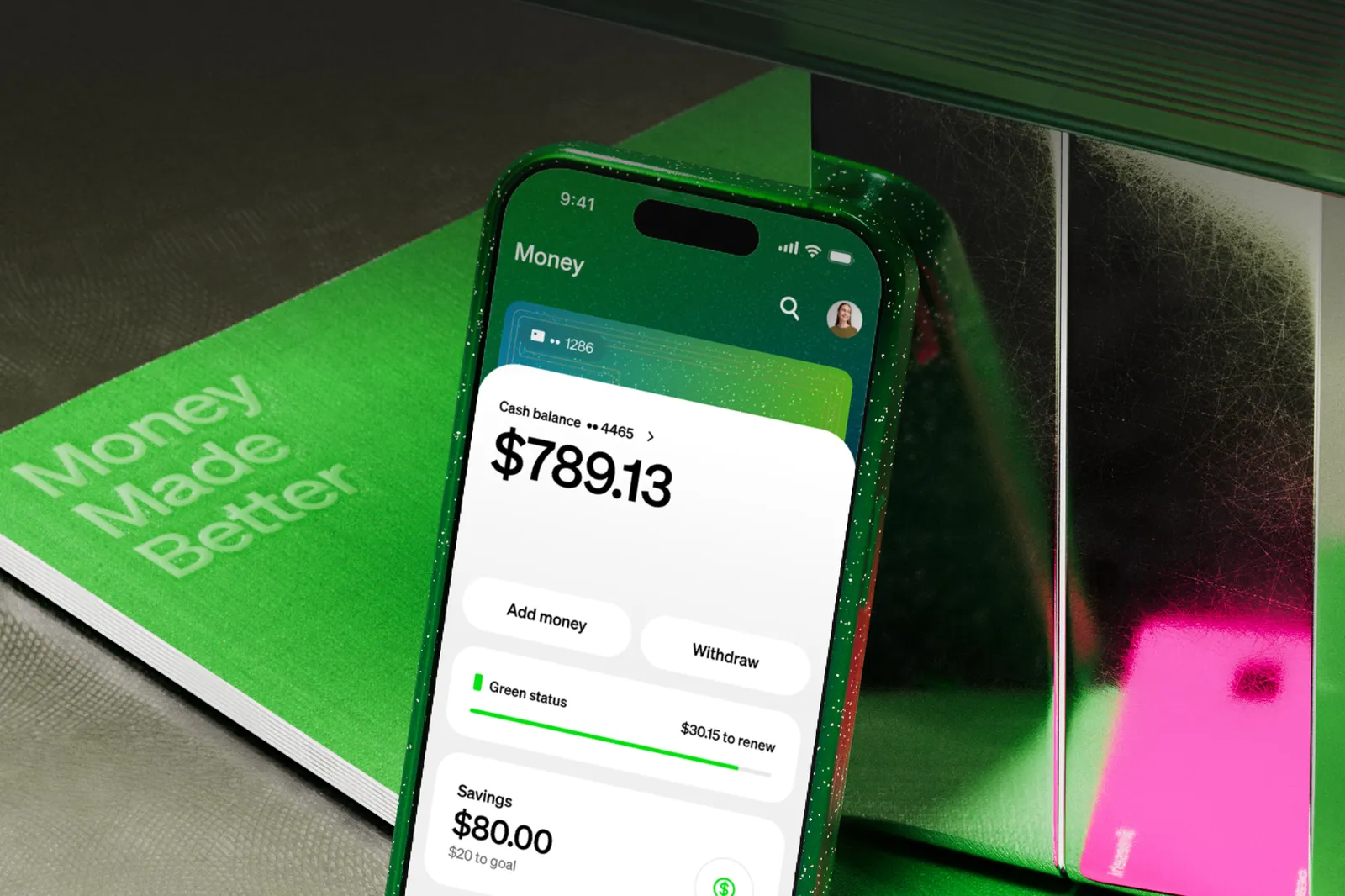

Ages removed from the era of email payments, today’s digital wallets serve an extensive menu of functions: they now can carry a digital passport and driver’s license; store concert tickets and cryptocurrency; trade stocks; enable lending; allow paycheck deposits; and hold virtual credit and debit cards that can tap rewards currency.

The wallets also, of course, provide payment at physical stores and online. Meanwhile, fintechs like Cash App parent Block and PayPal are expanding the wallets’ feature sets to attract new customers.

PayPal leads the mobile wallet pack

More than three-quarters of Americans (77%) surveyed used at least one of the three most popular U.S. wallets — PayPal, Cash App and Apple — during the third quarter, according to data from Statista, which surveyed about 60,000 U.S. adults online, ranging in age from 18 to 64.

On average, U.S. consumers made 11 monthly payments with their phones last year, compared to four in 2018, the Federal Reserve found in its annual survey of payment methods. “Households earning less than $25,000 per year and adults 55 and older relied more on cash than other cohorts,” the May Fed report said. “In contrast, adults aged 18 to 24 were more likely to pay with a mobile phone, using their phones for 45% of all payments.”

Globally, about 4.5 billion people use a digital wallet today, with the number expected to grow to 6 billion by 2029, according to a November report from Juniper Research.

Precise U.S. wallet usage figures are difficult to determine. Apple and Google, for example, group their wallet revenue figures within larger categories of sales, such as services and subscriptions, and neither releases user numbers. Block, however, discloses Cash App’s user growth by releasing the number of monthly active users.

The “larger participants” rule

After analyzing the rapid growth of digital wallets, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau in the Biden administration adopted a far more expansive view of what kind of guardrails were necessary for the industry. It followed through with a new rule boosting oversight of big tech companies that offer digital wallets in hopes of better safeguarding users.

Digital wallets are “doing a lot of bank-like activities, but their regulation is different from banks,” Lacey Aaker, a former CFPB policy analyst who worked on the now-defunct rule, said in an interview, noting the bureau’s rationale.

Many people use wallets and feature-rich financial apps as their primary source of banking. They don’t read deeply into companies’ disclosures about which funds may have federal deposit insurance or which debit payments are covered by the Electronic Fund Transfer Act, said Aaker, now a policy analyst with the nonprofit Consumer Reports.

“When we think about the everyday consumer, they don’t have time to read through all of the fine print,” she said. “They have lives and jobs.”

In November 2023, the CFPB proposed a rule — “Defining Larger Participants of a Market for General-Use Digital Consumer Payment Applications” — to address the perceived problems within the burgeoning financial technology industry.

“Big Tech and other companies operating in consumer finance markets blur the traditional lines that have separated banking and payments from commercial activities,” the bureau said in a press release announcing the rule. The bureau concluded that “this blurring can put consumers at risk, especially when the same traditional banking safeguards, like deposit insurance, may not apply.”

The bureau’s final rule, which was rolled back this year, would have extended supervision to seven “nonbank firms” that processed at least 50 million consumer transactions per year or about 98% of the 13.5 billion consumer payment transactions.

The CFPB did not identify any specific companies that would have been covered, nor did it include cryptocurrencies such as stablecoins within the rule. In December 2023, the bureau declined to reveal wallet data to Payments Dive under a Freedom of Information Act request, citing an exemption in the law for privileged and confidential information.

Nonetheless, the names surfaced this year when Congress moved to reverse the Biden-era CFPB rule. The Congressional Review Act resolution that overturned the regulation cited the seven largest digital wallet providers: namely, Google, Apple, Samsung, PayPal and its Venmo unit, Block’s Cash App and Meta’s Facebook.

The goal was “really trying to sort of figure out what is the right amount of regulation for these types of apps and these types of platforms, that has consumer protection that doesn’t stifle innovation,” Aaker said.

Most critically — to the industry’s indignation — the bureau aimed to impose supervisory examinations of nonbank technology behemoths’ operations, much the way regulators oversee banks.

Tech companies and retailers including Apple, Etsy, Google and Netflix vehemently opposed the rule, which took effect in January, weeks before the Trump administration took office. The tech firms filed a federal lawsuit to block the rule and lobbied lawmakers to rescind it under a congressional resolution, which passed and President Donald Trump signed in May.

The rule was a case of the bureau “getting over its skis,” said Jonathan Pompan, a Washington attorney with the law firm Venable, who advises financial services firms.

“It was trying to retrofit legacy consumer credit laws onto modern payment technology,” Pompan said. “And Congress recognized the mismatch and pulled the plug, while at the same time the administration was effectively placing [the CFPB] on life support.”

A regulatory smorgasbord

Digital wallets operate under a patchwork of state and federal laws, including their relationships with banks for deposit insurance on customer funds and obligations to consumers under the EFTA and Regulation E, said Laura Huntley, a managing director with FTI Consulting and a former banking regulatory attorney.

Banking regulators, the CFPB and the Federal Trade Commission also monitor financial firms for compliance with unfair, deceptive or abusive acts or practices.

The states monitor money senders under their money transmitter licensing rules, with enforcement powers. Many of the activities within wallets are also monitored by the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network for compliance.

Wallet and P2P companies are “highly regulated,” said Miranda Margowsky, a spokesperson for the Financial Technology Association, which counts PayPal and Block as members.

The firms are “directly regulated” by states as licensed money transmitters and their bank partnerships fall under the purview of federal supervision, she said. Wallet companies also are subject to several U.S. consumer protection laws, Margowsky noted.

Despite the death of the CFPB’s larger participant rule, “I don't think we could ever say wallets weren’t really regulated,” Huntley said in an interview. “They have been regulated and will continue to be regulated under exactly the same messy regime.”

“Even if the rule had gone into effect, the existing federal and state frameworks would have remained fully intact,” she added. “What we would have been doing there is just adding another supervisory layer on top of something that’s already pretty dense.”

The CFPB under former Director Rohit Chopra was “so aggressive,” she said. “We’re definitely seeing the pendulum having swung,” in terms of the bureau under Trump, Huntley said. “I think we got to a point there for a second where we said no risk was acceptable. And that’s crazy, because we’re in business.”

Currently, the bureau lists a dozen financial service areas where consumers may lodge a complaint, including with respect to “money transfers, virtual currency and money services.”

Beyond consumer payment services, the CFPB itself is facing critical questions about its future.

In November, the bureau said the Justice Department had determined its quarterly funding mechanism from the Federal Reserve was illegal and that its existing budget would lapse by early 2026. The agency also transferred its litigation and other legal enforcement work to the Justice Department.

Huntley and others pointed to the role that state attorneys general will increasingly play in consumer financial enforcement in the CFPB’s absence.

“I know we’ve been threatening this for a long time, but the states, they are coming,” Huntley said, noting that many former federal regulators at agencies like the CFPB and Office of the Comptroller of the Currency have moved into state roles.

Consumer trust and market policing

Unlike many developing markets such as Brazil, China and India, the U.S. has a long history of debit and credit card use, which in many ways has slowed the development of full-service financial wallets and their regulation, said Raynor de Best, a financial services analyst with the Hamburg, Germany-based market research firm Statista.

Emerging markets “skipped” the credit-and-debit era and designed payments around mobile wallets, said de Best, who studies the digital wallets market. “They wanted to push financial inclusion and they built the (payments) system along with the regulation at the same time,” he said.

Wallets and other payment platforms are deeply invested in safe products and competent customer service because of the financial consequences of shoddy products and trouble for their consumers, said Josh Istas, head of product for The Strawhecker Group, a financial services consulting firm.

“If that trust is abused in any way, shape or form that is against their major objective of growing their platforms,” Istas said. “There’s incentive from reputable good actors to ensure consumer protections.”

Google maintains dialogue with regulators, policymakers and industry partners to promote consumer protections given the growth of digital wallets, a Google Wallet executive, Dong Min Kim, said in an email from the company. Google also believes that the industry needs consistent regulatory frameworks to foster trust and innovation, he said.

Recent changes at Cash App — incorporating digital currencies and lending to a broader group of customers — are meant to respond to customer demands reflecting “how they participate in the modern economy,” Owen Jennings, Block’s business lead, said Nov. 13 during a product release event.

“Cash App is on this journey from what used to be a simple peer-to-peer app into what’s now a full-fledged financial platform that can allow a customer to run their financial life,” Jennings said. “The level of trust that’s required in order to cross that chasm is much higher.”

Apple and Samsung did not respond to several requests for comment; Block, Google and PayPal declined requests for an executive interview.

Block’s Cash App is one of the few wallets that publicly touts its growth, with 58 million active users in September.

The risks of skipping the fine print

The wallets and apps ecosystem “has evolved to that point where companies who are offering digital banking need to become a bank to really fall into the framework that makes most sense for the service they’re offering,” said Kyle Rosen, head of Americas for Thunes, a Singapore cross-border software firm with U.S. customers that include MoneyGram and Western Union.

“The industry generally leads the regulator in terms of what occurs,” Rosen noted. “There’s innovation and then we need to regulate around it.”

Consumers are unaware of details such as the differences between a bank and fintech or which kinds of funds movements are covered by the EFTA, said Tony DeSanctis, a senior director at Cornerstone Advisors, a bank consulting firm.

Some of the larger wallet risks for consumers revolve around which fintechs or neobanks enter the market, DeSanctis said. Ultimately, it will be about how responsibly new players act.